New Bone Formation in the Maxillary Sinus Using Only Absorbable Gelatin Sponge

Dong-Seok Sohn, DDS, PhD,* Jee-Won Moon, DDS,† Kyung-Nam Moon, DDS, MSD,‡ Sang-Choon Cho, DDS,§ and Pil-Seoung Kang, DDS!

Purpose: The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the predictability of new bone formation in the maxillary sinus using only absorbable gelatin as the graft material.

Patients and Methods: Seven patients (9 sinus augmentations) were consecutively treated with sinus floor elevation by the lateral window approach. The lateral bony window was created using a piezo- electric device and the schneiderian membrane was elevated to make a new compartment. After 18 resorbable blast media surfaced dental implants were simultaneously placed, absorbable gelatin sponges were loosely inserted to support the sinus membrane over the implant apex and the bony portion of lateral window was repositioned to seal the lateral window.

Results: After uncovering the implants an average of 6 months after placement, new bone consolidation in the maxillary sinus was observed on radiographs without bone graft. Two implants were removed due to failed osseointegration on uncovering. Failures were caused by insufficient initial stability.

Conclusion: This study suggests that placement of a dental implant in the maxillary sinus with a gelatin sponge can be a predictable procedure for sinus augmentation.

© 2010 American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

J Oral Maxillofac Surg 68:1327-1333, 2010

The widespread use of dental implants for replace- ment of missing teeth has led to complex surgical procedures to increase the amount of available bone. Placement of dental implants on the edentulous pos- terior maxilla could present difficulties due to a deficient posterior alveolar ridge, unfavorable bone qual- ity, and increased pneumatization of the maxillary sinus.1,2 Increased implant failure rates in the poste- rior maxilla are related to insufficient residual height and poor bone quality.3,4 Such problems have been overcome by increasing the alveolar height with max- illary sinus augmentation.5,6 The lateral window ap- proach is a commonly used technique for maxillary sinus augmentation, especially when the initial alveo- lar bone height cannot ensure the primary stability of simultaneous placement of implants.5-7 Numerous studies have documented the technical details for the lateral window method, and these procedures have shown clinical predictability.6-9 The sinus augmenta- tion procedure is usually accomplished by creating a lateral bony window followed by elevation of the schneiderian membrane. The space created between the maxillary alveolar process and the elevated schneiderian membrane is typically filled with au- tografts, allografts, xenografts, alloplasts, or combina- tions of different graft materials to maintain space for new bone formation.6,10-15 Several studies have re- ported that factors such as the volume of graft material, the kinds of bone graft, and the amount of autog- enous bone affect the amount of new bone formation,

and most of these studies have shown a correlation between the success of the bone graft and the success of dental implants.6,10-15

Elevating the maxillary sinus membrane and graft- ing with bone substitutes has become routine treat- ment over the past 40 years, and some studies have reported successful bone formation and osseointegra- tion in cases of performing sinus membrane elevation without bone grafts.16-19

The aim of this study was to verify new bone formation by radiologic results by application of only an absorbable gelatin sponge (Cutanplast; Mascia Brunelli Spa, Milano, Italy) in the space between the elevated schneiderian membrane and simultaneously placed implants.

Patients and Methods

PATIENT SELECTION

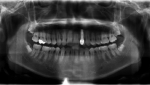

The present study population consisted of 7 con- secutive patients, 6 men and 1 woman, 40 to 75 years of age (mean age, 56.1 years). All patients were in- formed about the treatment procedure and provided written consent for participation, and this study was approved by the institutional review board of the Catholic Medical Center of Daegu. The patients pre- sented with a partially or fully edentulous atrophic maxilla with sinus pneumatization. Preoperative ex- aminations with panoramic views and dental cone- beam computed tomographic scans (Combi, Point- nix, Seoul, Korea; or Implagraphy, Vatec, Kyungi, Korea) were performed. Available bone volume, bone quality, and any existing sinus pathology were evalu- ated on these radiographs. The bone height of the remaining alveolar ridge was 1.5 to 7.0 mm (average, approximately 5.0 mm; Table 1). Patients were con- secutively treated with sinus floor elevation by the lateral window approach.

Patients who had previous failed sinus augmenta- tions, who exhibited pathologic findings or had a history of maxillary sinus diseases or operations, or whose medical conditions might increase surgical risks of the research protocol were excluded.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Prophylactic oral antibiotics (cefditoren pivoxil 300 mg 3 times/day; Meiact, Boryung Pharmacy, Seoul, Korea) were used routinely, beginning 1 day before the procedure and continuing for 7 days. Surgery was performed under local anesthesia through maxillary block anesthesia using 2% lidocaine that includes 1:100,000 epinephrine. Flomoxef sodium (Flumarin; Ildong Pharmaceutical Co, Seoul, Korea) 500 mg in- travenously was administered 1 hour before surgery. Maxillary sinus floor elevation by the lateral approach was completed in all participants. The approach to the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus was followed after the elevation of a mucoperiosteal flap according to surgical needs. A piezoelectric saw (S-Saw; Bukboo Dental Co, Daegu, Korea), connected to a piezoelec- tric device (Surgybone; Silfradent Srl, Sofia, Italy), was used with copious saline irrigation to create the lat- eral window of the maxillary sinus (Fig 1). The ante- rior vertical osteotomy was made 2 mm distal to the

FIGURE 1. A piezoelectric saw (S-Saw; Bukboo Dental Co, Daegu, Korea), connected to a piezoelectric device (Surgybone; Silfradent Srl, Sofia, Italy), was used to create the lateral window of the maxillary sinus in all cases (patient 4)

FIGURE 2. After elevation of the schneiderian membrane and placement of implants, an absorbable gelatin sponge (Cutanplast; Mascia Brunelli Spa, Viale Monza, Italy) 70 ! 50 ! 1 mm was divided into 3 pieces and inserted into spaces anterior and poste- rior to the implants and below the elevated schneiderian membrane (patient 6).

FIGURE 3. The lateral bony window was repositioned without additional procedures (patient 6).

anterior vertical wall of the maxillary sinus and the distal osteotomy was made approximately 20 mm away from the anterior vertical osteotomy. The height of the vertical osteotomy was approximately 10 mm. The anterior and inferior osteotomy line was created perpendicular to the inside of the maxillary sinus lateral wall, and then superior and posterior osteoto- mies perpendicular to the sinus wall were performed. This design of osteotomy facilitates the precise re- placement of the bony window as a barrier over an inserted gelatin sponge in the maxillary sinus. The bony window was detached carefully to expose the sinus membrane. The schneiderian membrane was

carefully dissected from the sinus floor walls with a flat blunt-edged instrument. Dissection of the sinus membrane was continued to reach the medial and posterior walls of the sinus cavity. After elevation of the schneiderian membrane and placement of im- plants (SybronPRO XRT implants; Sybron Implant So- lution, Grendora, CA), an absorbable gelatin sponge (70 ! 50 ! 1 mm; Cutanplast) was divided into 3 pieces. The pieces were folded and inserted into the new compartment of the maxillary sinus. One piece of gelatin sponge was placed anterior to the implant site, 1 posterior to the site, and 1 directly above the implant apex to support the membrane (Fig 2). The bony portion of the lateral window was repositioned to prevent soft tissue ingrowth into the sinus cavity and to promote new bone formation from the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus (Fig 3). Flaps were sutured using interrupted mattress polytetrafluoroethylene su- tures (Cytoplast; Osteogenic Biomedical, Lubbock, TX) to achieve passive primary closure. Patients were instructed not to blow their nose for 2 weeks after surgery and to cough or sneeze with an open mouth. Preoperative prophylactic antibiotic therapy was con- tinued postoperatively for 7 days, and the sutures were removed 14 days postoperatively. After sinus augmentation, postoperative panoramic radiographs and cone-beam computed tomographic scans were taken immediately after surgery. An average of 6 months was allowed for the implants to integrate. The implants were then uncovered and panoramic radio- graphs and dental cone-beam computed tomographic scans were obtained to assess new bone formation around the implants. Implants were loaded with pro- visionals for 3 months before the final prostheses were delivered.

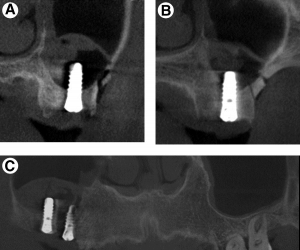

FIGURE 4. Postoperative cone-beam computed tomographic scans revealed the sinus was filled with blood clots and voids under the elevated schneiderian membrane. A, Implant corresponding to the maxillary right second molar. B, Implant corresponding to the maxillary right first molar. C, Panoramic computed tomogram (patient 6).

Results

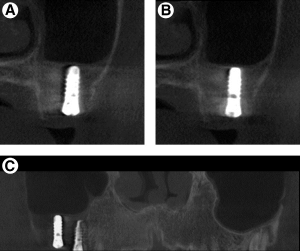

Postoperative cone-beam computed tomographic has reported similar or better success than of implants placed using a conventional protocol with no grafting scans revealed that the sinus was filled with blood procedure.6 However, Lundgren et al16 reported succlots and voids under the elevated schneiderian mem- brane (Fig 4). No adverse events were recorded dur- ing the healing period in any patient. There were no cessful new bone formation and osseointegration of implants in cases of sinus membrane elevation with- out bone grafts, with radiographic and in vitro histo 17 signs of infection. Two implants failed before loading logic results. Palma et alcompared the histologic due to insufficient initial stability when placed into an extraction socket. The schneiderian membrane was perforated in 1 case. The absorbable gelatin sponge was used for managing these perforations. After un- covering the implants, on average 6 months after placement, new bone consolidation was observed on radiographs and cone-beam computed tomographic scans (Fig 5). The newly formed maxillary sinus floor was observed around the implant apex in all cases including the failed implant sites. No apparent differ- ences were observable on imaging of the augmenta- tion with nonperforation or perforation sites. The patients maintained stable implant prostheses during their final prostheses (Fig 6).

Discussion

One long-term study on the clinical success of im- plants placed into the augmented maxillary sinus with variable bone grafts, regardless of graft materials used, results of sinus membrane elevation and simultaneous placement of implants with and without adjunctive autogenous bone grafts in primates. The results showed no differences between membrane-elevated and grafted sites with regard to implant stability, bone-to-implant contacts, and bone area within and outside implant threads histologically in animals.

Nedir et al18 reported that elevation of the sinus membrane alone without the addition of bone graft- ing material can lead to bone formation beyond the original limits of the sinus floor from osteotome- mediated sinus floor elevation. Sohn et al19 reported favorable new bone formation in the maxillary sinus without bone graft and clinical implant success with in vivo histologic evidence for the first time.

FIGURE 5. New bone consolidation was observed on computed tomographic scans. The former sinus floor disappeared and newly formed sinus floor and new bone formation were observed. A, Implant corresponding to the maxillary right second molar. B, Implant corresponding to the maxillary right first molar. C, Panoramic computed tomogram (patient 6).

The absorbable gelatin sponge inserted loosely un- der the elevated sinus membrane acted as a space maintainer for new bone formation in the maxillary sinus as an alternative to bone filler in this study. All cases showed new bone formation in the new compartment of the maxillary sinus; even the elevated sinus membrane showed repneumatization around the implant apex. In cases of bone grafts into the maxillary sinus, bone graft materials have the role of filler, resulting in space in the sinus. However, grafted bone volumes also adapt considerably in shape and volume due to repneumatization of the maxillary sinuses, with a resorption rate of 0.4% to 54%.20-23 In the present study, 2 implants failed during the uncovering procedure due to insufficient osseointe- gration. The failed implants could not be inserted with sufficient primary stability in the extraction socket, and the residual bone height was shorter than 2 mm in 1 of the sites. Achievement of primary sta- bility depends on adequate preparation of the bone site to receive the implant and demands strict adher- ence to surgical protocols.24 Implants with deficient initial stability are susceptible to micromotion at the bone-to-implant interface, which may affect the bone- healing process and result in fibrous encapsulation.25

Previous studies have shown that implants with surface treatment exhibit greater bone-to-implant

FIGURE 6. Panoramic radiograph shows the augmented right maxillary sinus and fixed bridges in situ.

contact mainly in the early stages of osseointegra- tion and in areas of low-quality bone.26,27 Sybron- PRO XRT implants with resorbable blast media sur- faces were placed in the present study. Piattelli et al28 reported that the resorbable blast media sur- face could be considered more osteoconductive than a machined surface. The study, with scanning electron microscopy and electron spectroscopy for clinical analysis, showed that implant surface treat- ment can improve in vitro cellular adhesion and proliferation.27 However, surface treatment pro- cesses can leave the processing material embedded in the implant surface as residual contaminants dur- ing beading or grit blasting.29 Such a problem could be avoided by the use of calcium phosphate media. Although the residual particles existed, they could be absorbed or attached to surrounding bone.28 The barrier membrane between graft materials and the overlying soft tissue is necessary to prevent growth of fibrous connective tissue in the augmented space.30,31 The lateral bony window was replaced after augmentation of the maxillary sinus and simul- taneous placement of implants in this study. The re- placeable bony window made by the piezoelectric saw could be precisely repositioned because of the tilted osteotomy into the sinus, highly controlled os- teotomy, and minimal bone loss during osteotomy. Lundgren et al16 used an oscillating saw to create the lateral window as a barrier for sinus augmentation. The application of a conventional oscillating saw in creating a lateral bony window is irritating to patients because of the loud noise during surgery. Moreover, access to the oral cavity may be limited. Hence, use of a piezoelectric device is recommended to create a lateral bony window to obtain direct visibility over whole osteotomies, highly precise bone cut by micrometric, and linear vibrations.19,32-36 The precisely created bony window prevents the replaceable bony win- dow from dropping into the maxillary sinus cavity.19,34

Whether or not bone grafting is performed in the maxillary sinus, the replaceable bony window acts as a homologous barrier over the new compartment under the elevated maxillary sinus.19 Lundgren et al16 reported that there are several advantages to using a replaceable bone window, according to the principle of guided tissue regeneration. Sohn et al19 demon- strated that there are no clinical differences in new bone formation in the maxillary sinus between the group using nonresorbable membrane and the group using replaceable bony window to seal the lateral window, according to histologic data in humans. However, a homologous bony window is free from viral cross-contamination of animal or human origin and saves the surgical cost of purchasing barrier mem- branes. Homologous bony windows not only prevent soft invasion into the grafted site but also act as osteoinductive/osteoconductive substrates for new bone formation in the sinus, accelerating new bone formation in the grafted/nongrafted sinus.

In conclusion, elevation of the sinus membrane, simultaneous placement of implants, and insertion of gelatin sponges demonstrate new bone formation through clinical and radiographic evaluations. New bone formation was verified by stabilization of the elevated sinus membrane from the tenting effect of placement of dental implants and absorbable gelatin sponge without any bone graft material. This study shows that there is great potential for new bone formation in the maxillary sinus without the use of additional bone grafts. It is suggested that long-term follow-up often is required for confirmation of the stability of this procedure.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr Paul Maupin for his valuable assistance in editing this article.