Ahmed Elkhaweldi, BDS, MS*

Dong Hyun Lee, DDS

Wendy CW Wang, BDS

Sang-Choon Cho, DDS

* Former Resident, New York University College of Dentistry, New York, NY.

** Private Practice, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

*** Resident, New York University College of Dentistry, New York, NY.

◊ Clinical Professor and Director, Ashman Department of Periodontology and Implant

Dentistry, New York University College of Dentistry, New York, NY.

Correspondence to: Dr. Ahmed Elkhaweldi, 36-04 31st Avenue, Apt #2B, Astoria, NY,

11106.

Email: ae815@nyu.edu.

Elkhaweldi, Ahmed. Lee, Dong Hyun. Wang, Wendy CW. Cho, Sang-Choon.

Abstract:

Introduction: Although many studies have been conducted to compare the survival rate of dental implants with different degree of roughness, but there is scarcity of studies that compare the survival rate of implants with two different surfaces and have geometrically identical body design.

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to evaluate and discuss the difference in survival rate between two geometrically identical implant groups with two different surfaces to help understand the effect of implant surface roughness on their survival rate.

Materials and methods: The data in this study were obtained retrospectively from the consecutive analysis of anonymous database at New York University College of Dentistry. The clinical records for 161 patients (102 males, and 59 females) were gathered. The study included 280 implants of the same identical geometrical design and had either RBM or SLA surface. The follow up time since the implants were restored ranged from 4 to 32 months (average 18 months).

Results: A total of nine implants have failed in six patients. The overall survival rate of the 280 implants was 96.7%. The first group included 167 RBM implants while the second group included 113 SLA implants. Only one implant from the SLA group was

lost compared to eight implants that have failed from the RBM group. The SLA implants group had higher survival rate of 99.1% while RBM implants group found to had a survival rate of 95.2%.

Conclusion: In the limitation of this study, geometrically identical implants with either RBM or SLA surface have a very comparable survival rate at least on the short term. However, the SLA surface implants seems to be superior in the posterior maxilla with poor bone quality.

Elkhaweldi, Ahmed. Lee, Dong Hyun. Wang, Wendy CW. Cho, Sang-Choon.

Introduction:

The early experimental studies in the field of implant dentistry suggested that an inert titanium implant could be surgically inserted in an edentulous alveolar ridge. Once the implant in place, sequence of soft and hard tissue healing around it will follow. Eventually the implant can be utilized in anchoring dental prostheses.(1) Branemark group was the first to report that titanium implants could be incorporated within the bone through oxide layer and as a result, the two could not be disconnected without fracture. This phenomenon has been referred to as osseointegration or osteointegration, which mandate a direct bone-to-implant contact with absence of fibrous tissue encapsulation.(2)

Ever since, the bone-to-implant interface has been studied extensively with great emphasis on the implant surface characteristics. On one hand, it is believed that osseointegration between bone and titanium implants can be achieved and maintained for a long period of time regardless of their surface characteristics.(3) On the other hand, the majority of in-vivo and in-vitro studies found that an implant surface with some degree of roughness has a better and an accelerated process of healing toward achieving osseointegration.(4) It has been shown that there is a positive relationship between the degree of roughness and the speed of osseointegration. One study showed that implants with surface roughness (Sa) ranging between 0.5-1μm have a weaker bone response

concluded that smooth (Sa 0.5μm) and minimally rough (Sa 0.5–1μm) surfaces show reduced and slower bone responses than rougher surfaces. Interestingly, moderately rough (Sa 1–2μm) surfaces showed better bone responses than highly rough surfaces (Sa

>2μm).(6) It was previously shown that implants with rougher surface has more bone-to- implant contact at period 3-6 weeks than implants with less roughened surface. In addition to that, a recent in vitro study found that rough surfaces (1-2μm) are more preferable by osteoblasts as they increased the gene expression for Cbfα1 mRNA of osteoblast. Osteoblast also showed an enhanced adherence and propagation on rough surfaces compared to machined surface implants.(7,8)

Different techniques have been utilized to alter the surface topography of dental implants. These techniques are usually applying either additive or subtractive concepts. One of the early used techniques is the Titanium Plasma Spray (TPS) which is an additive technique results in an increase of the surface area up to six times(9). Hydroxyapatite (HA) plasma spray is also one of the early additive techniques developed for coating dental implants with biomaterials to change their surface characteristics. The early results of this

technique were very promising as it enhanced the osseointegration of dental implants, but follow up studies showed that the use of plasma-sprayed HA to coat dental implants has increased the clinical failure which was attributed to the delamination of the thick HA layer and to the uncontrolled rate of dissolution of deposited phases.(10, 11) The additive surfaces became less preferred by clinicians than the subtractive surfaces. Long term follow up studies for these surfaces have shown increased risk of peri-implantitis and

eventually led to decline in their survival rate.(6,12) TPS surfaces have also shown poor response to treatment of peri-implantitis. Consequently, subtractive surfaces like Sand blasted and acid etched (SLA), Resorbable Blast Media (RBM), and Dual Acid Etching (DAE), which have moderate roughness, became more popular.(13)

Currently, the two major subtractive surfaces in clinical use is the SLA surface and the RBM surface.(9) SLA surface is created first by sandblasting with large grit particles then followed by acid etching to remove the remaining particles and further increase the roughness. The SLA surface has surface average roughness (Sa 1.78μm).(9, 14) One

study that looked at the survival rate of SLA implants found that after 10 years period of follow up, these implants had 98% survival rate.(15) Simone et al also reported survival rate for SLA surfaced dental implants of 82.94% after a follow up period of 10-16 years.(16) Resorbable blast media surface (RBM) is formed through propelling resorbable coarse bioceramics (calcium phosphate) particles on titanium metal substrate followed by passivation process aiming to increase the level of roughness and enhance the osseointegration capability of the implant. One of the advantages of this technique is gained via the use of calcium phosphate particles that eliminates the risk of leaving contaminating debris after blasting. Leaving contaminated surface is considered a

common drawback for using other less biocompatible blasting materials. Resorbable blast media surface possesses average roughness around 1.5μm.(17,18) In one animal study, RBM surface had a higher bone to implant contact after 90 days than either of TPS, HA coated, and smooth surface implants.(19) As far as RBM surface survival rate is a concern, studies have reported comparable survival rate of 95.37% after 7 years of follow

up period.(20)

With regard to comparing the effect of the implant surface characteristics on the survival rate, the literature is rich with large numbers of studies investigating this issue but all of the mentioned previous studies cited in this article have compared different implant surfaces on different geometrical design. For example, Al Nawas et al compared the survival rate of Turned surfaced implants from Nobel Biocare to double acid etched surfaced implants from Biomet 3i. After periods of 49 months follow up, no difference in the survival rate has been found between the two surfaces.(21) In another similar study

by Khang et al that compared the survival rate of machined surfaced implants to double acid etched surfaced implants found that the latter had a 9% higher survival rate of

95%.(22)

According to the author’s knowledge, there is a scarcity of clinical studies that compare the survival rate of two surfaces with the same exact body design. One study by Li et al compared the removal torque and the bone response of two identical implants with either SLA surface or machined and acid etched surface and found that SLA surface achieves a better bone anchorage and had more than 5% higher stiffness of the removal torque test.(23) Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate and discuss the survival rate of SLA surface to RBM surface for implants with identical geometrical design.

Materials and Methods

The data in this study were obtained retrospectively from the consecutive analysis of anonymous database at New York University College of Dentistry. The clinical records for 161 patients (102 males, and 59 females) were gathered. These patients have received a total of 280 implants all of which had the same body design with diameter ranging from

4.1mm to 4.8mm and length ranging of 9 to 13mm (average 11mm). The age of the patients in this study ranged from 21 to 81 (average 55.3 years). Implants were placed in the period between March 2012 to February 2014. The study included 167 implants with RBM surface and 113 implants with SLA surface. All of the survived implants are restored and in function at the time of this study. The follow up time since the implants were restored ranged from 4 to 32 months.

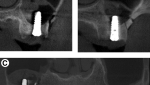

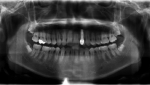

The study included only patients who had received implants of the same identical geometrical design and had either RBM or SLA surface (EBI Inc., Kyungsan, South Korea), (Figure1, 2). The surface roughness parameters for each surface represented in Ra and Sdr are shown in table 1 (A, B).

Patient who had uncontrolled systemic disease were excluded from this study. All the patients included in this study were periodontal disease free. The bone quality was considered poor when the patient had type IV bone (Zarb and lekholm) and had less than

15Ncm primary stability. All of the implants were surgically placed by the same surgeon

(SC), while another restorative dentist restored them.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22, (Chicago IL-CHECK). Continuous data are presented as means and their associated standard deviation and categorical data are presented as percentages. Group-differences for continuous variables were assessed using the t-test (normal distributed variables), analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Mann-Whitney U test (non-normal distribution). For categorical variables, Chi-square or Fischer’s Exact Tests were used.

We performed our analysis in three steps. First, we used two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with implant failure as the dependent variables and the type of implant surface as the independent variable. In the second step, we estimated the mean implant failures after adjusting for relevant co-variables. The relevant co-variables were defined as the ones that showed to be statistically significant between the SLA and RBM surfaces and they were time of follow-up, diameter and diabetes.

Third, we determined the magnitude of the effect of the implant surface type on implant failures by using logistic regression analyses in which implant failure was the dependent variable and implant surface type and the relevant covariates (as defined above) were the independent variables. 5% level of significance was used.

Results: Statistical results

Characteristics of the population

Overall, this study evaluated 280 implants that were followed up for a mean of 19.2 month (SD=6.62) and a range of 4-32 months (Figure 3). However, there was a significant difference in the time of follow up between SLA and RBM implants. Age, gender, smoking, length of the placed implants, and area of placement (posterior maxilla vs. not-posterior maxilla) did not differ between the two surface groups (Table 2). Diameters of the placed implants were higher in the SLA group and more diabetes subjects were present in the RBM group (Table 2).

Implant failure in the two surface groups

When we compared implants with SLA and implants with RBM surface, mean failed implants tended to be lower in the SLA group compared to RBM group (0.01 vs. 0.05; p=0.07). Due to the time of follow up, implant diameter and the number of implants placed in diabetes subjects were different between the two implant surface groups, we performed ANCOVA with these parameters as covariates. The adjusted means were statistically significant (p=0.039). These results showed that the mean failure is lower in SLA group and diabetes, smoking and follow-up time did not account for this difference.

Using logistic regression, we estimated the magnitude of the implant surface effect on predicting implant failures. Since the covariates age, gender, smoking, anatomical area, implant length did not differ between the two groups, they were not included in the final

model. However, diabetes and time to follow-up were statistically significant different between the two groups and therefore were included in the models. As shown in Table 3, three models were constructed. In our crude analysis the implant surface type was a significant predictor of the implant failures at a trend level (OR=5.64; p=0.11). When in sequential models the follow up time and diabetes were added to the models the OR became even stronger (OR=6.40 and 6.52 respectively) suggesting that these parameters did not affect the surface effect on implant failure. Pertaining to our results we observed a significant effect of follow-up time on the implant failure independent of the surface effect. Our results showed that the follow-up time was a significant predictor of the implant failure: with each year increase in the follow up was a significant odds of not- failures. In other words, as the time passes the odds of failures decreased (p=0.009).

Clinical Results

The two groups of either RBM surfaced implants or SLA surfaced implants were analyzed. A total of nine implants have failed in 6 patients. The overall survival rate of the 280 implants was 96.7%. The first group included 167 RBM implants while the second group included 113 SLA implants. (Table 4) Only one implant from the SLA group was lost compared to eight implants that have failed from the RBM group. The SLA implants group had a cumulative survival rate of 99.1% while RBM implants group found to have a cumulative survival rate of 95.2%. (Table 5 A, B), (Figure 4)

Implants survival in different location:

Anterior maxilla:

Twenty RBM implants were placed in the anterior maxilla. Three of them were placed in grafted sites while the rest were placed in pristine bone. The survival rate for these RBM implants was 90%. The two implants from this group have failed both of them were placed in grafted sites. In comparison two SLA implants were placed in the anterior maxilla. One implant was placed in pristine bone while the other was placed in grafted site. The survival rate of these implants was 100%.

Posterior maxilla:

Eighty-eight RBM implants were placed in the posterior maxilla. Forty-eight of them were placed in grafted sites utilizing either sinus elevation or guided bone regeneration. The survival rate for these implants was 95.4%. Four implants in this group have failed all of which were placed in grafted sites. On the contrary, sixty-three SLA implants were placed in the posterior maxilla. These implants had survival rate of 98%. Twenty-seven

of these implants were placed in grafted sites utilizing either Guided bone regeneration of sinus augmentation procedure. Only one implant has failed in this group, which was also placed in previously grafted area.

Anterior mandible:

In this location eleven RBM surfaced implants were placed. None of these implants was lost to the time of this study. No SLA surfaced implants were placed in this location.

Posterior mandible:

All of the implants that were placed in the posterior mandible were placed in pristine bone. Forty-eight RBM surfaced implants had a survival rate of 95.8% with two implants

failures. While forty-eight SLA surfaced implants that were placed in the posterior mandible had 100% survival rate with no failures.

Cement-retained verses screw-retained

Screw retained restoration was utilized in the majority of implants’ restorations. Thirty- nine implants were restored utilizing cement-retained restorations all of which are still in function at the time of this study. All of the failures have occurred in the screw-retained restorations with eight failures in the RBM surface group and one failure in the SLA surface group.

Single unit verses multi units

Out of two hundred and eighty implants placed, seventy-two of them had a single unit restoration. The rest of the implants were supporting fixed dental prosthesis. The survival rate of implants supporting single unit restoration was 100% for the RBM group as well as the SLA group. All of the nine failures have occurred in implants supporting fixed dental prosthesis.

Discussion:

The purpose of this study was to evaluate and discuss the difference in survival rate between two geometrically identical implant groups with two different surfaces to help understand the effect of implant surface roughness on their survival rate. This study found that there is a direct relationship between the poor bone quality and the increased

rate of failures especially for RBM implants which were placed in augmented bone. Four out of eighty eight RBM surfaced implants have failed in grafted posterior maxilla. These failed implants were the most distal implants that supported fixed dental prostheses. The remaining forty implants, which were placed in native bone in the posterior maxilla, have all survived. Barone et al have also reported that implants in grafted posterior maxilla have a higher failure rate compared to the implants placed in pristine bone in the

posterior maxilla.(24) However, their study did not address the effect of the implant surface on the survival rate.

In this study sixty-three SLA implants were placed in the posterior maxilla, only one of them has failed. The failure has occurred in a smoker and again the implant was the most distal implant in three units maxillary fixed dental prosthesis. The author suggests that the rougher SLA surface have a compensating effect in areas with poor bone quality through the improved bone-implant-contact which might increase the survival rate at such area compared to less rough RBM surface especially during the first months of osseointegration. This finding has been supported with many previous studies, which investigated the effect of surface roughness on the survival rate of dental implants in poor bone quality. In one study compared the survival rate of machined and double acid etched

implants. It was stated that machined implants had higher failure rate than double acid etched in areas of poor bone quality.(22) Stach et al have also reported similar results analyzing the survival rate of the same previous two surfaces.(25) In a more recent long term retrospective study of 19 years follow up, it was shown that minimally rough surface implant had higher failure rate than moderately rough surface implants (Machined Vs. SLA). The failures were more correlated to implants placed in type IV bone. Although the study found that rough surface implants had more failures in the long term than smooth surfaces, which was correlated to the occurrence of per-implantitis assessed by probing depth, bleeding on probing, suppuration, Plaque Index, and the presence of saucer- or crater-shaped bone loss in radiographs.(26)

The survival rate of the RBM implants in the anterior area was 90%, which is low with regard to the short observation period of this study. It has been shown before that the anterior maxilla follows the posterior maxilla in the tendency of implant failures.(27) In addition to that, the two failed implants in the RBM group were placed in previously grafted sites. On the contrary, there were only two SLA implants placed in this area and they both still in function.

The posterior mandible RBM implants had survival rate of 95.8%, as two implants from this group has failed in one patient, while SLA implants had a 100% survival rate. The same survival rates of SLA implants in posterior mandible have been reported previously including short implants.(28) Only two implants from the RBM group have failed. Based on this result, the author suggests that implant surface degree of roughness between the two groups does not seem to have an effect on implant survival rate at the posterior

mandible at least for the short term outcomes.

Forty-eight RBM surfaced implants and twenty-seven SLA implants were placed in grafted posterior maxilla. Five out of total nine failures have happened in this location. Interestingly, about 50% of the failures occurred in the most distal supporting implant. The number of failure had indirect relationship with the amount of remaining crestal bone before the augmentation. It has been reported in the literature that the most posterior implant receives the highest occlusal forces. The combination of poor bone quality and excess forces on the posterior implant seemed to have a major negative effect on the survival especially for the RBM surface group.

In addition, six out of the nine failures have occurred when the implants were opposing to natural teeth. Parel et al have also reported an increase in the percentage of implant

failure in posterior maxilla with poor bone quality where implants are opposed by natural dentition. They attributed the failures to the irregularities in the occlusion of the natural dentition.(29)

This study included twenty-seven smoker subjects. Only three of the implants placed in those subjected had failed. All of the three implants were RBM surfaced implants. Although, previous studies have reported increased risk of implant failure in smokers.(30) However, in this study the author relates the failure of these implants to local factors like bone quality and occlusal factors rather than to smoking or any other systemic factors.

One possible explanation for this is that the short-term follow up of this study may have prevented the smoking from manifesting a significant effect on the survival rate.

It has been stated before that implant failures occur as a cluster in small number of patients rather than random incidence. This means that some groups of patients have high risk of losing more implants than others. Multiple factors have been suggested to influence the increased failure rate in these patients. In this study, three RBM implants have failed in one patient. After the removal of these implants, Three SLA implants have been placed. Until the time of this study all of them are still in satisfactory status. Burt et

al, have reported that if an implant failure has happened in a patient there is more than 30%

chance that this patient will lose another implant.(31)

Conclusion

In the limitation of this study, geometrically identical implants with either RBM or SLA surface have a very comparable survival rate at least on the short term. However, the SLA surface implants showed fewer tendencies to fail compared to RBM surfaced implants.

References:

- Branemark PI, Breine U, Adell R, et al. Intraosseous anchorage of dental prostheses. I. Experimental studies. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg 1969; 3:81.

- Mavrogenis AF, Dimitriou R, Parvizi J, Babis GC. Biology of implants osseointegration. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2009 Apr-Jun; 9 (2): 61-71.

- Iezzi G, Vantaggiato G, Shibli JA, Fiera E, Falco A, Piattelli A, Perrotti V. Machined and sandblasted human dental implants retrieved after 5 years: a histologic and histomorphometric analysis of three cases.

Quintessence Int. 2012 Apr; 43 (4): 287-92.

- Novaes AB Jr, de Souza SL, de Barros RR, Pereira KK, Iezzi G, Piattelli A. Influence of implant surfaces on osseointegration. Braz Dent J. 2010; 21(6): 471- 81.

- Kunzler TP, Huwiler C, Drobek T, Vörös J, Spencer ND. Systematic study of osteoblast response to nanotopography by means of nanoparticle-density gradients. Biomaterials. 2007 Nov; 28 (33): 5000-6.

- Wennerberg A, Albrektsson T. Effects of titanium surface topography on bone integration: a systematic review. Clin Oral Impl. Res. 20 (Suppl. 4), 2009; 172–184.

- Fan Z, Jia S, Su JS. Influence of surface roughness of titanium implant on core binding factor alpha 1 subunit of osteoblasts. 2010 Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. Aug; 45 (8): 466-70

- Buser D, Schenk R, Steinemann S, Fiorellini J, Fox C, Stich H. Influence of surface characteristics on bone integration of titanium implants. A histomorphometric study in miniature pigs. J Biomed Mater Res

1991; 25:889–902

- Wennerberg A, Albrektsson T. on implant surface: A review of current knowledge and opinions. Int J

Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2010 Jan-Feb; 25 (1):63- 74.

10.Block MS, Gardiner D, Kent JN, Misiek DJ, Finger IM, Guerra L. Hydroxyapatite-coated cylindrical implants in the posterior mandible: 10-year observations. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1996 Sep-Oct;

11 (5): 626-33.

11.Watson CJ, Tinsley D, Ogden AR, Russell JL, Mulay S, Davison EM. A 3 to 4 year study of single tooth hydroxylapatite coated endosseous dental implants. Br Dent J. 1999 Jul 24; 187 (2): 90-4.

12.Esposito M, Hirsch J-M, Lekholm U, Thomsen P. Failure patterns of four osseointegrated oral implant systems. J Mater Sci Mater Med 1997: 8: 843–847.

13.Roccuzzo M, Bonino F, Bonino L, Dalmasso P. Surgical therapy of peri-implantitis lesions by means of a bovine-derived xenograft: Comparative results of a prospective study on two different implant surfaces. J Clin Periodontol 2011; 38:738–745.

14.Coelho PG, Granjeiro JM, Romanos GE, Suzuki M, Silva NR, Cardaropoli G, Thompson VP, Lemons JE. Basic research methods and current trends of dental implant surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2009 Feb; 88(2): 579-96.

15.Buser D, Janner SF, Wittneben JG, Brägger U, Ramseier CA, Salvi GE. 10-year survival and success rates of 511 titanium implants with a sandblasted and acid-etched surface: a retrospective study in 303 partially edentulous patients. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2012 Dec; 14 (6): 839-51.

16.Simonis P, Dufour T, Tenenbaum H. Long-term implant survival and success: a 10-16-year follow-up of non-submerged dental implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010 Jul; 21 (7): 772-7.

17.Sanz A, Oyarzún A, Farias D, Diaz I. Experimental study of bone response to a new surface treatment of endosseous titanium implants. Implant Dent. 2001; 10(2): 126-31

18.Ricci, J.L., Kummer, F.J., Alexander, H. and Casar, R.S., “Embedded Particulate Contaminants in

Textured Metal Implant Surfaces,” J. Appl. Bio, Vol. 3,1992.

19.Novaes AB Jr, Souza SL, de Oliveira PT, SouzaAM. Histomorphometric analysis of the bone-implant contact obtained with 4 different implant surface treatments placed side by side in the dog mandible. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2002 May-Jun; 17 (3): 377-83.

20.Kim YK, Kim BS, Yun PY, Mun SU, Yi YJ, Kim SG, Jeong KI. The seven-year cumulative survival rate of Osstem implants. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014 Apr; 40 (2): 68-75.

21.Al-Nawas, B., Hangen, U., Duschner, H., Krum- menauer, F. & Wagner, W. (2007) Turned, ma- chined versus double-etched dental implants in vivo. Clinical Implant Dentistry & Related Re- search 9:

71–78.

22.Khang, W., Feldman, S., Hawley, C.E. & Gunsol- ley, J. (2001) A multi-center study comparing dual acid-etched and machined-surfaced implants in various bone qualities. Journal of Periodontology 72:

1384–1390.

23.Li D, Ferguson SJ, Beutler T, Cochran DL, Sittig C, Hirt HP, Buser D. Biomechanical comparison of the sandblasted and acid-etched and the machined and acid-etched titanium surface for dental implants. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002 May; 60 (2): 325-32.

24.Barone A, Orlando B, Tonelli P, Covani U. Survival rate for implants placed in the posterior maxilla with and without sinus augmentation: a comparative cohort study. J Periodontol. 2011 Feb; 82 (2): 219-26.

25.Stach RM, Kohles SS. A meta-analysis examining the clinical survivability of machined-surfaced and

osseotite implants in poor-quality bone. Implant Dent. 2003; 12 (1): 87-96.

26.Han HJ, Kim S, Han DH. Multifactorial evaluation of implant failure: a 19-year retrospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2014 Mar-Apr; 29 (2): 303-10.

27.Tolstunov L. Implant zones of the jaws: implant location and related success rate. J Oral Implantol.

2007; 33 (4): 211-20.

28.French D, Larjava H, Ofec R. Retrospective cohort study of 4591 Straumann implants in private practice setting, with up to 10-year follow-up. Part 1: multivariate survival analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2014 Aug 19.

29.Parel SM, Phillips WR. A risk assessment treatment planning protocol for the four implant immediately loaded maxilla: preliminary findings. J Prosthet Dent. 2011 Dec; 106 (6): 359-66.

30.Twito D, Sade P. The effect of cigarette smoking habits on the outcome of dental implant treatment. Peer J. 2014 Sep 2;2:e546.

31.Weyant R, Burt B. An assessment of survival rates and within-patient clustering of failures for endosseous oral implants. J Dent Res 11:2-8.

RBM SLA

Figure 1. Two geometrically identical implants, 4.1mm X 11mm, the RBM surfaced implant on the left and the

SLA surfaced implant on the right.

Figure 2. SEM of RBM on the left and SLA on the right at 2000x magnification

| Ra | High | Middle | Low |

| Left | 1.00 | 1.09 | 1.49 |

| Center | 1.21 | 1.17 | 1.29 |

| Right | 1.33 | 1.43 | 1.41 |

| Overall | 1.27 | SD | 0.16 |

| Sdr | High | Middle | Low |

| Left | 206.79 | 172.00 | 250.94 |

| Center | 196.37 | 178.35 | 186.68 |

| Right | 174.58 | 220.17 | 189.20 |

| Overall | 179.23 | SD | 25.46 |

Table 1. A) RBM surface Ra, and Sdr

| Ra | High | middle | Low |

| Left | 1.44 | 1.15 | 1.22 |

| Center | 1.13 | 1.18 | 1.19 |

| Right | 1.46 | 1.05 | 1.04 |

| Overall | 1.21 | SD | 0.15 |

| Sdr | High | middle | Low |

| Left | 206.79 | 172.00 | 250.94 |

| Center | 196.37 | 178.35 | 186.68 |

| Right | 174.58 | 220.17 | 189.20 |

| Overall | 197.23 | SD | 25.46 |

Table 1. B) SLA surface Ra, and Sdr

Figure 3. The follow up period of all implants

| SLA Surface

N= |

RBM Surface

N= |

p–value | |

| Age [Mean (SD)] | 55.3 (11.30) | 57.70 (10.31) | 0.165 |

| Gender [N (%)]: Female | 40 (36.7) | 52(32.1) | 0.433 |

| Follow up [Mean (SD)] | 17.58 (5.93) | 20 (7.11) | 0.002 |

| Posterior Maxilla

[N (%)] |

61 (54) | 90 (53.9) | 0.988 |

| Smoking | 17 (15) | 29(17.4) | 0.607 |

| Diabetes | 4 (3.5) | 16 (9.6) | 0.054 |

| Diameter | 4.72 (0.40) | 4.12 (0.12) | 0.00 |

| Length | 10.10 (0.63) | 10.05 (0.23) | 0.48 |

| Failure | 0.01 (0.09) | 0.05 (0.21) | 0.07 |

| Failure Frequency | 1 (0.9) | 8 (4.8) | 0.069 |

Table 2. Mean (SD) = unadjusted means and standard deviations.

Table 3. Odds ratios for the implant surface type as relates to implant failures.

OR 95%CI p-value

|

Surface type

– Crude (only surface)

– Model1 (variables: Surface type, and follow up)

– Model2 (variables: Surface type, follow up and diabetes

| Anterior maxilla | Posterior Maxilla | Anterior Mandible | Posterior Mandible | |

| RBM | 20 | 88 | 11 | 48 |

| Failed | 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| Survival Rate | 90% | 95.40% | 100% | 95.80% |

| SLA | 2 | 63 | 0 | 48 |

| Failed | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Survival Rate | 100% | 98.40% | N/A | 100% |

Table 4. The overall survival rate of each group of implants in different locations in the mouth

|

Interval Time (months) |

Implants in Interval |

Implants Lost |

Implants Survived |

Cumulative Survival |

|

0-3 |

167 |

0 |

167 |

1 |

|

4-6 |

167 |

2 |

165 |

0.98 |

|

7-12 |

165 |

6 |

159 |

0.95 |

|

13-18 |

159 |

0 |

159 |

0.95 |

|

19-24 |

159 |

0 |

159 |

0.95 |

| 25-36 | 159 | 0 | 159 | 0.95 |

Table 5. A) Cumulative survival rate of RBM surfaced implants

|

Interval Time (months) |

Implants in Interval |

Implants Lost |

Implants Survived |

Cumulative Survival |

|

0-3 |

113 |

0 |

113 |

1 |

|

4-6 |

113 |

0 |

113 |

1 |

|

7-12 |

113 |

1 |

112 |

0.99 |

|

13-18 |

112 |

0 |

112 |

0.99 |

|

19-24 |

112 |

0 |

112 |

0.99 |

| 25-36 | 112 | 0 | 112 | 0.99 |

Table 5. B) Cumulative survival rate of SLA surfaced implants